This article is by its nature self-promotion for Julien’s Auctions (where I serve as COO), but I believe it is consistent with my past articles sharing news and insights about Star Wars with followers, so I’m making an exception in this case, as I am in a unique position to share new information about Star Wars. I wanted to put a spotlight not so much on our lots in an upcoming auction, but on Jack Warford and his story behind some of the iconic photography of original model starships from the original Star Wars in 1977. All of this background was completely unknown to me prior to working on bringing some prints and original photos to auction this year.

I do from time to time get very involved with some of the material that we bring to auction at Julien’s. I’ve been working with Sue Warford, widow of Jack Warford, for most of this year with a very unique collection.

I had never heard of Jack Warford before she contacted me, but once I saw his work, I was very familiar with some of the images that he created with the original Star Wars.

This was somewhat similar to when I had worked with Colin Cantwell, bringing his never before seen concept artwork for Star Wars to auction back in 2014.

In the case of these beautiful prints that I worked on this year, unfortunately, Jack Warford had passed away in 2018. But I have had the pleasure of getting to know his widow, Sue, who has been an amazing person to become acquainted with over the past six months.

Sue, now 84, worked with Jack in their photography business. Both Magnum Photographers, they had photographed many in and out of Hollywood, including Ronald Regan, Clint Eastwood, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and more.

Because she does not have a computer and is not online even via smart phone, we discussed Jack’s work on Star Wars at length over the phone before I ever saw images of his work, but I knew right away what iconic images she must have been describing.

When I finally received the limited number of prints that he made of his work in 1977 (most blown up to 16×20), this was affirmed. I felt a bit like I was uncovering long lost treasure, as many were familiar, yet different, and I am fairly certain a number of the images have never been published.

Along with the Star Wars prints were other photography examples from his career, as well as some amazing shots of Jack (some by Sue herself).

Most interesting was that Sue kept a letter with an account of his experience working on Star Wars… in his own words.

While not a traditional auction house thing to do, I was determined to share his story within our printed and online catalogues, to in some manner memorialize his account for fans and historians.

I have created a PDF excerpt from our catalogue of the relevant pages for those who are just interested in the story and getting a sense of the images, which you can download here:

Again, this is just his first-hand, personal account of his own experience, which obviously cannot be verified one way or another with the passage of time. But in my searching the Internet and asking some Star Wars-savvy fans and collectors about Jack Warford, no one knew who I was talking about or his role in working on the film, so I feel it is important to in some way record his history, which otherwise might have been completely lost.

His story is also copied below:

When The Force Was With Me

By Jack Warford

George Mather was a good friend of mine. He was a general, all-around film person who belonged to Screen Actor’s Guild and the Director’s Guild, was occasionally a non-union cinematographer and usually had his fingers in more pies than Little Jack Horner. When he needed a photographer, he called me, whether it was to shoot a casting portfolio of his current girlfriend, and he had a lot of those, or to do working portraits of all the staff members of an entire studio. On one particular occasion, he called to see if I would be free on a certain Sunday in 1977 to take some pictures of some models.

I had photographed many models for their portfolios, for ads, and I was a staff photographer for the short-lived fashion magazine, California Girl, so I said “Sure.” He told me to call Gary Kurtz, the producer of this picture he was working on for details. I did. It seems that the models in question were not the breathing, posing, photogenic female kind, but models of space ships for a science fiction movie shooting at this rented barn near the Van Nuys Airport that had been dubbed Industrial Light and Magic. The pictures were to be for publicity and promotion. I calculated a price for that and agreed at five hundred for the afternoon.

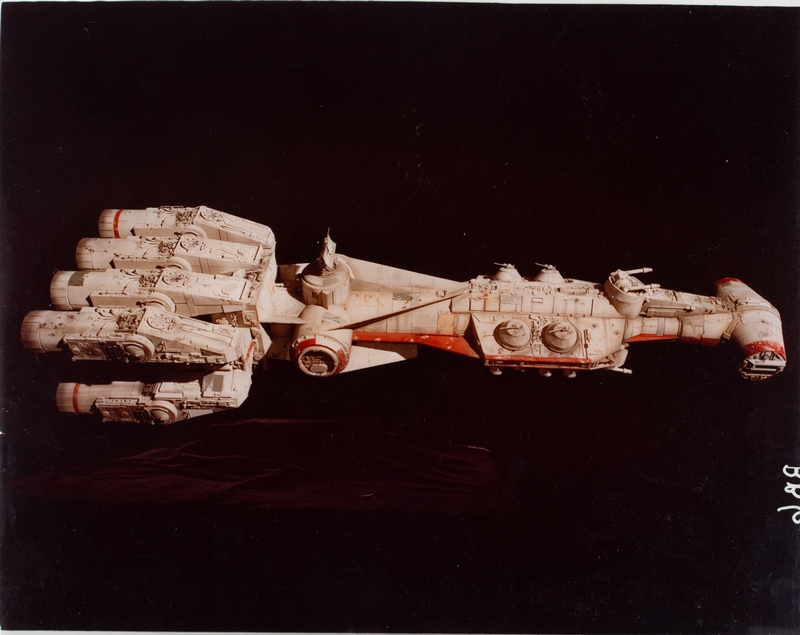

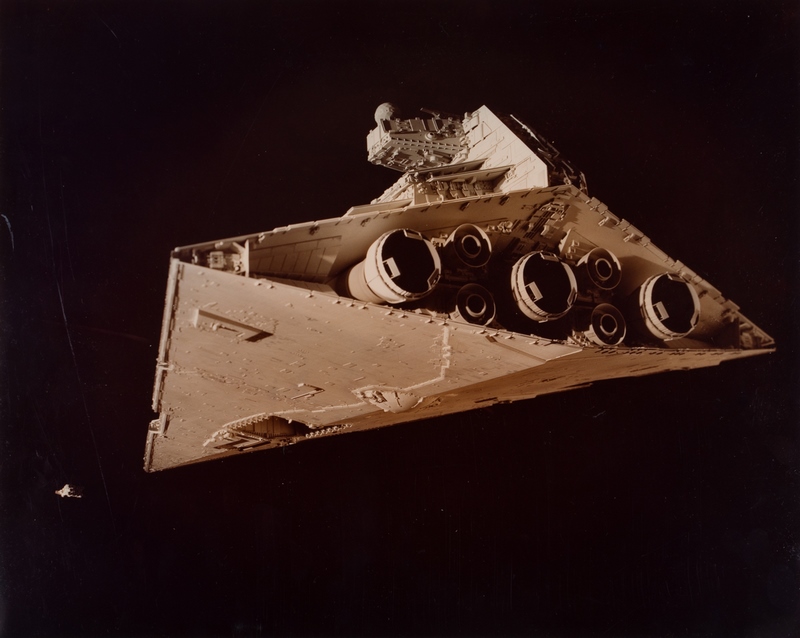

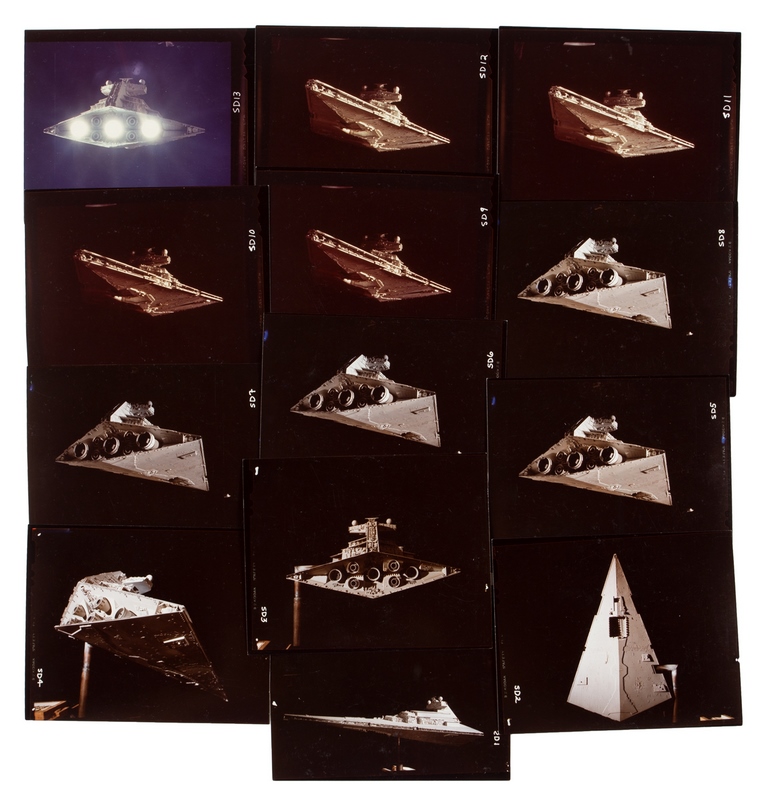

When I arrived at the studio, accompanied by my wife, Sue, and my next door neighbors, Tom and Peggy Marks, who had been invited to come and watch by George, we were given coffee and the grand tour of the works in progress by John Dykstra, the special photographic effects supervisor. The model makers had been having such a wonderful time building the space ships that they had fallen behind in production and schedule and were over budget. When George was hired as production manager and whip cracker, only one shot had been completed, the shot of the pod with C3PO and R2D2 (named for a roll of magnetic tape, roll 2, dialog 2) blasting down to the planet below from the blockade runner. The part of the movie with the live action had been completed months before and the actors had all gone home. The Millennium Falcon that had served for a set in England for the actors, only showing a quarter of the whole ship, had cost less than a third of the three foot diameter model used by Industrial Light and Magic, henceforth referred to as ILM, for the full-body shots in action. On the day we arrived, they had just finished what turned out to be the opening shot of the movie. The three-foot long model of the Imperial Cruiser was upside down on a plexiglass pedestal with a blue neon light inside chasing a two inch model of the blockade runner. For the reverse shots of the blockade runner, carrying Princess Leah and the two droids, they used the largest model they made, being over six feet long. In some photographic processes, called Blue Screen, blue will disappear, and it is easy to strip in another piece of film. It goes back to the dawn of movies, in The Great Train Robbery when the train comes rolling by the open window in the telegraph office. If you cover an actor’s face and hands in blue, presto, the invisible man. It explains why newscasters can never wear blue shirts.

John showed me the setup of the shot they had just taken. The camera was mounted on a dolly running on railroad tracks beside the models and the wide angle lens was only a couple inches above the model as the computer oozed it by very slowly. Nearby was a monitor. He turned it on. The picture was in black and white negative, inverted so you were looking at it from underneath instead of above. The tiny blockade runner flashed across the screen and then the imperial cruiser came by. It kept coming. It still kept coming until it passed by and the engines were visible I was completely blown away. “You just got my three bucks, (the cost of a movie ticket then)” I said. In most, if not all, of the shots of the ships, it was the camera that moved in a predetermined path, operated by instructions from a computer, not the ships. Backgrounds would be added later along with the blasts from the engines.

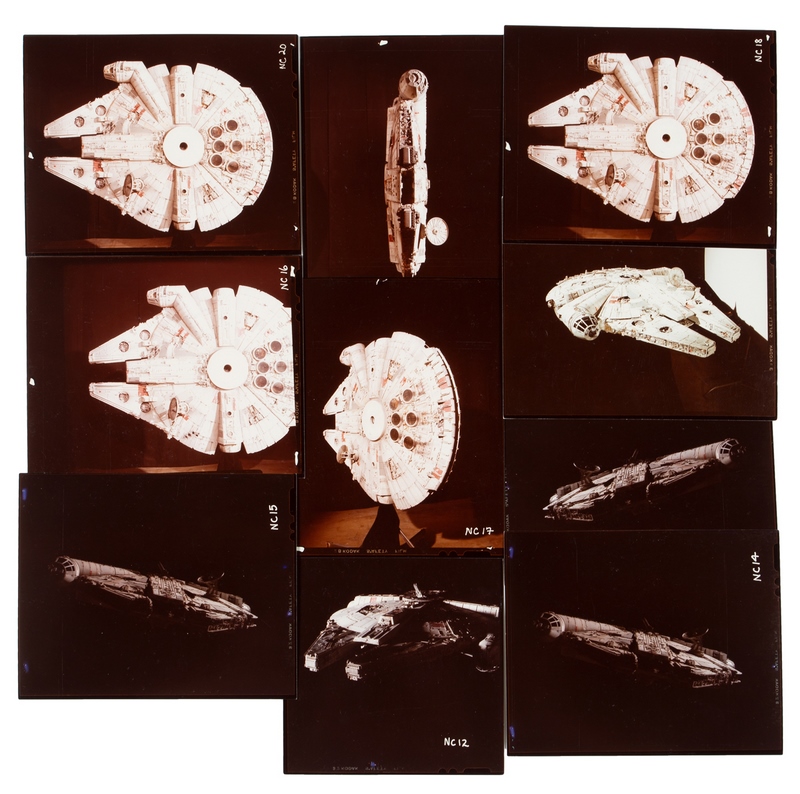

ILM had made a deal with a Japanese model maker to send them all the rejects of their model cars or whatever. For example, where the mandibles or jaws of the Millennium Falcon join the main body between the upper and lower plates, you can see the oil pan and transmission of a model Mercedes Benz. The sprues that held the plastic parts together during the casting were put to work as piping.

The model makers at ILM had a wonderful time playing, as evidenced by the missing plate on the Millennium falcon with a skeleton curled up inside that no one would ever see – one of the reasons George Mather was called in as expediter.

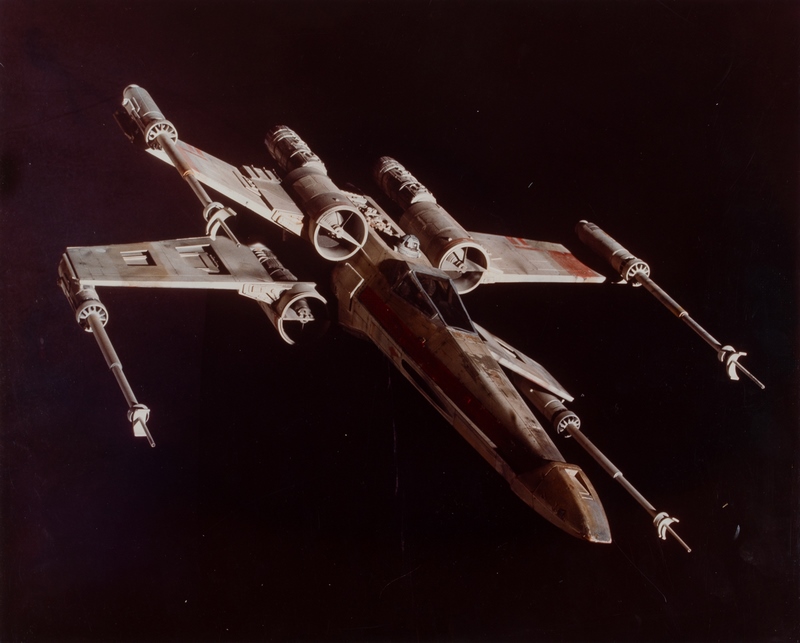

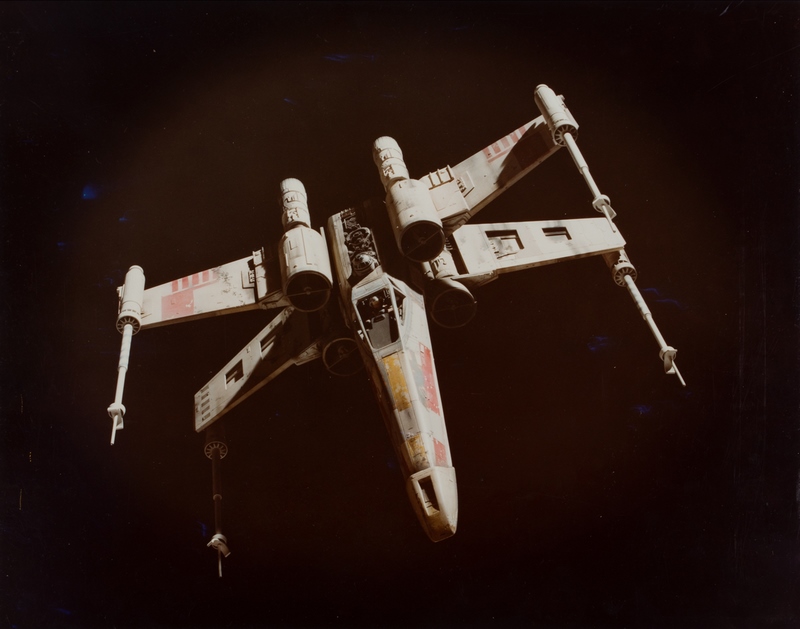

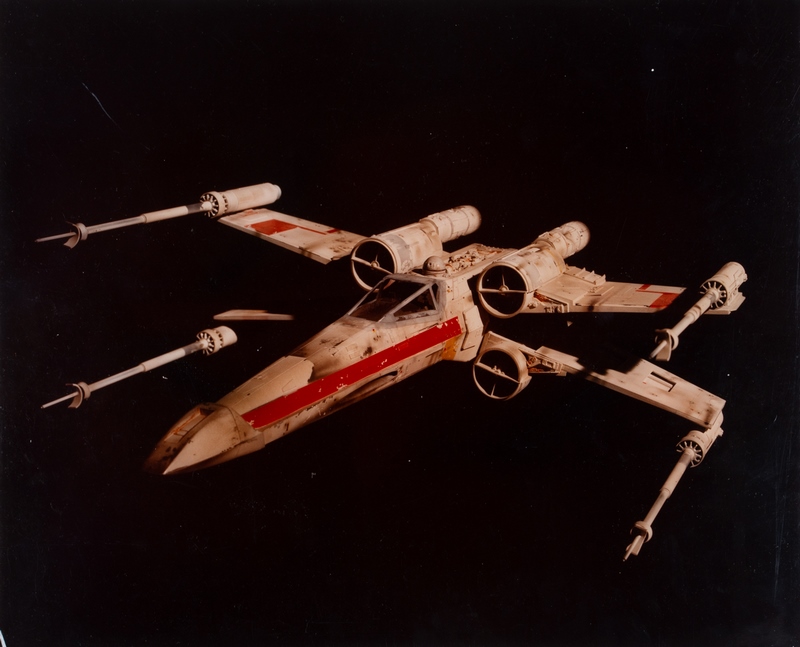

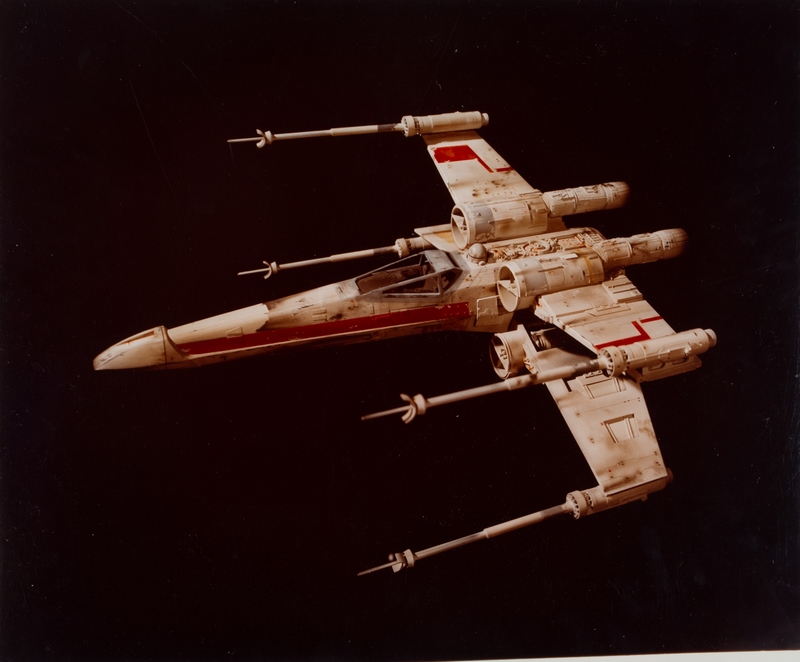

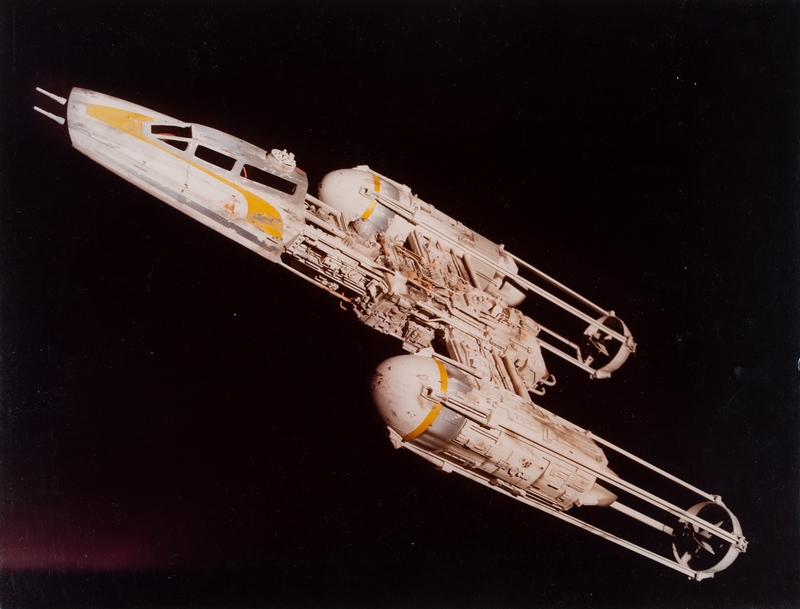

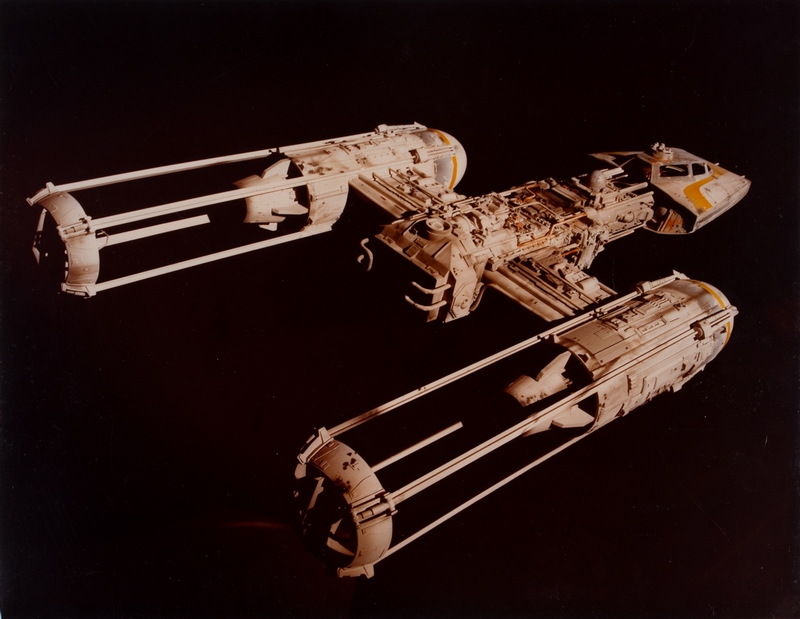

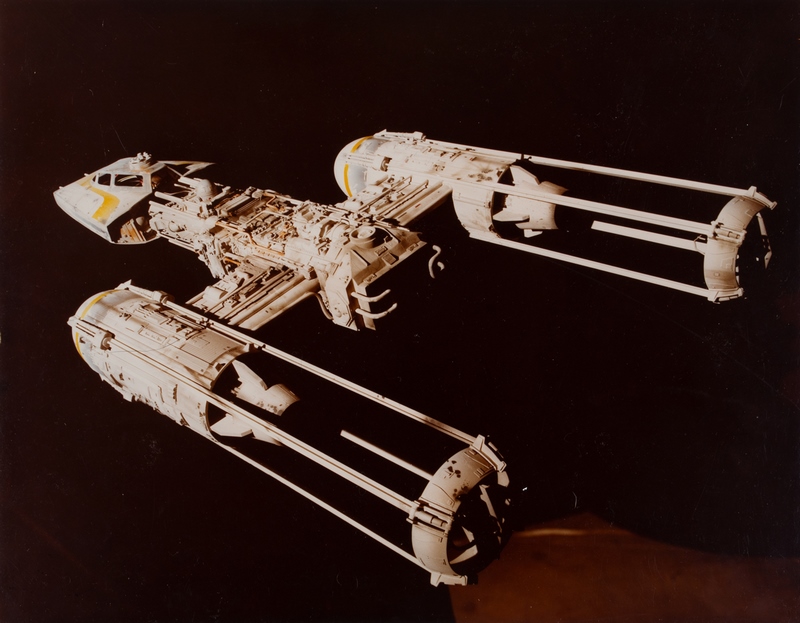

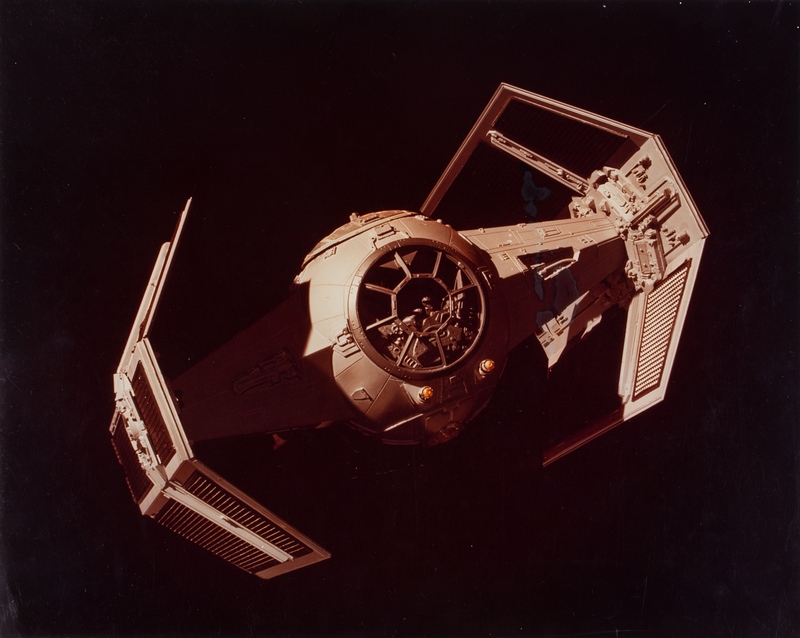

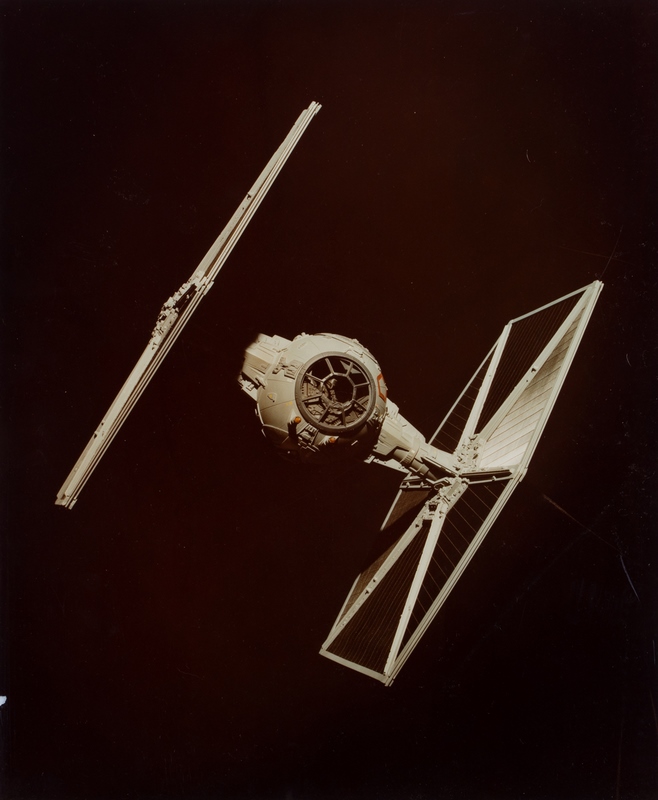

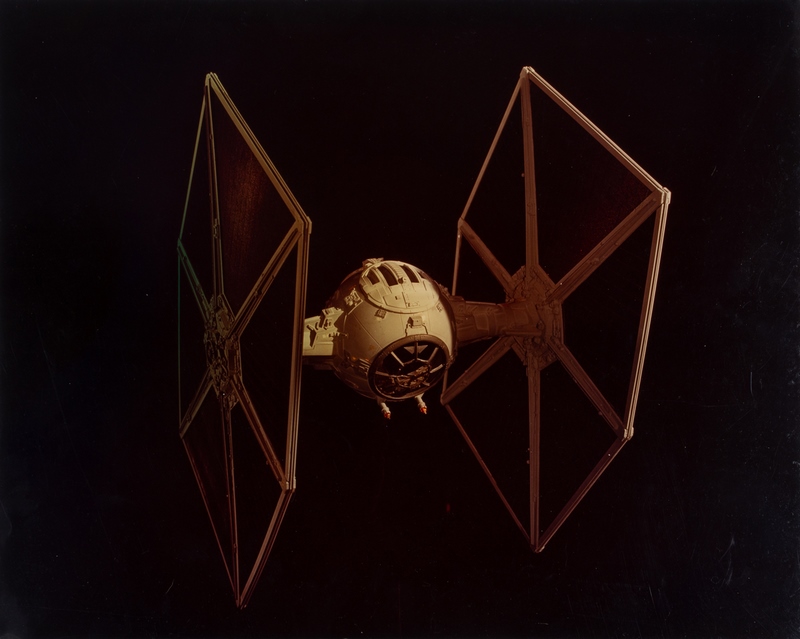

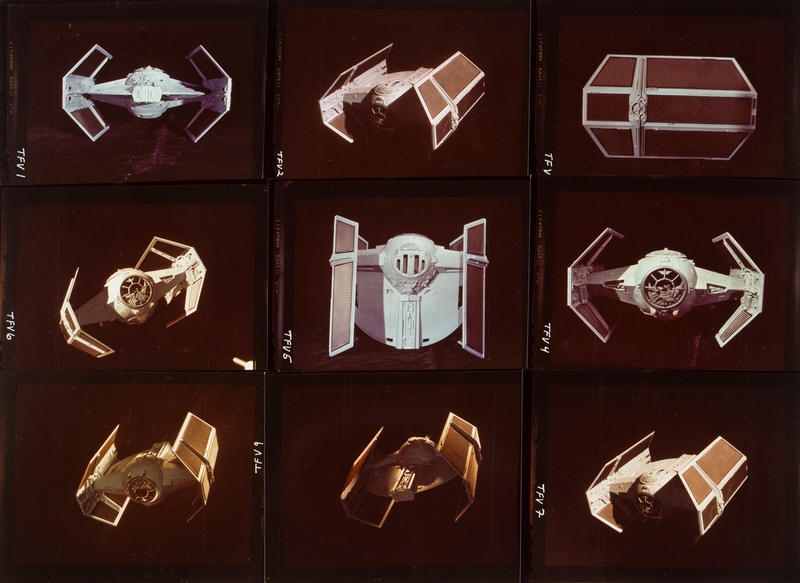

It was time to go to work. Gary Kurtz showed me the different models he wanted shot – the Millennium Falcon, several different X-wing fighters, some Y-wing fighters, the set up shot with the tiny blockade runner and the Imperial Cruiser, the full size blockade runner, used in reverse shots of the interception, which was the largest model they had made, being over six feet long, and some surface shots of various scales of the surface of the Death Star to use as backgrounds. Whatever lighting I needed would be provided. Since this was supposed to be outer space where there is no atmosphere to diffuse the light, I used one large floodlight for a single source with no fill, as if the model were lit by a nearby star. I set up my Linhoff 4 X 5 camera, using a six-inch Golden Dagor lens, about as fine a photographic setup as is available. After setting up each shot as if the ships were in action, not merely static models, I called in Gary to take a look at the lighting and setup before I tripped the shutter. One shot I was particularly proud of was of an X-wing fighter, front on with one laser on a wingtip pointed right at the camera. This shot was the one that wound up on lunch buckets, game box covers, and t-shirts as well as publicity shots and posters and may have been the most published photograph of 1977. An animated copy showed up in the Star Wars computer game.

The next day, I took the Ektacolor negatives to Spectra Color Lab in Burbank. My wife and I were going out of town on a shoot, so we arranged to have the negs and the contact proofs picked up. Upon our return, I called George. He said he was appalled I rushed to his office to take a look and some of the shots had blue flashes on them, something I had never seen before.

I found out this was caused by the high degree of static electricity at the studio that made sparks when the dark slides were pulled out of the film holders. I called Gary Kurtz, apologizing and offering to do a reshoot. He said the pictures were just fine and since the images would be stripped out and stuck on starfield or Death Star backgrounds, there would be no problems since most of the flashes were not on the ships bodies and the others could easily be taken out. I asked Gary Kurtz if I could borrow the negatives and make some prints With Gary’s blessing, I made several copies of each of what I considered to be the best shots, mostly in 16 X 20 with a few 8 X 10’s.

It would be awhile before I heard from Lucasfilm again. And then when I did it was an invitation to the cast and crew screening of Star Wars, not THE Star Wars as it was under the shooting title, at the Director’s Guild Theater on Wilshire Boulevard, lunch to follow at Dr. Munchie’s. George and Marcia Lucas had just finished editing the film, and no one else had seen so much as a working print. It was not Episode IV, A New Hope, but just Star Wars. There was no scene between Han Solo and Jabba the Hut; that would be added later.

There was a burst of applause from the cast and crew on the opening shot that I described, another when the modified elephants made up like bantas appeared and when the stars took on a Doppler effect as the Millennium Falcon jumped into faster than light speed. When the lights came on, it was plain that the audience was more than pleased with what they had done, Almost everyone, that is. The feeling was jubilant, Mark Hamil was surrounded by a heard of friends and relatives, but as the theater emptied, Harrison Ford, shoulders hunched, hands in pockets, staring at the floor in front of him, slouched down the aisle very much the loner wearing a cloud of gloom. Wearing our “May the Force Be With You” buttons that had been passed out as we walked in, we proceeded to Dr. Munchie’s where we were adequately wined and dined. After eating, Sue and I were sitting on some steps talking to John Dykstra when Harrison Ford ambled up, still wearing his dark cloud. He had enjoyed maybe one too many glasses of wine. I asked him why he was so depressed. He replied that he hadn’t worked as a actor in nine months since the live action was finished and he didn’t know if he would ever work again. We all tried to cheer him up in vain. He was convinced this was the bottom point in his life and his career. We all know he did work again, quite a few times and the world may have gained a movie star, but it lost a wonderful carpenter.

A few days later the film opened and was an immediate smash hit. My pictures, uncredited, were splashed all over Time magazine that called it “The best film of the year.” The edition of Newsweek put the first thorns in my side, when my pictures were credited to Richard Edlund, the special effects cinematographer.

I wrote a letter to Gary Kurtz suggesting that I put out a special edition of signed and numbered photographs I heard from Lucasfilm asking if I thought they should get a slice of the pie, to which I agreed, and I later heard from Fox that I should forget the whole idea. At least I had the prints I had made for myself.

Another thorn appeared when I found my photographs used on lunch buckets, t-shirts, and games, and all sorts of ancillary items going along with the movie. Another was to see a set of three fighters made from the same image with that tell-tale electric blue splash on their sides advertising Nikkor lenses. The original agreement was for publicity and promotion and this was going way beyond that. Star Wars may have been shot with Nikkor lenses, but the illustration was not. I called Gary Kurtz to complain. I was informed that everyone who worked for ILM was an employee whether for one day or the whole run and the product of their labors with all rights was the property of Lucasfilm/Twentieth Century Fox. Oh, yeah? If I was an employee instead of an independent contractor, where was my W-2 form? It was time to call a lawyer.

It would seem that according to copyright laws, while the image may belong to the creator, the rendering belongs to the photographer.

In the course of the lawsuit amidst depositions, questions and answers, there were some numbers discovered on the edge of the negatives. No one had the faintest idea what they were for. Richard Edllund excluded the photos of the surface of the Death Star and such as had blue static electricity streaks and claimed all the rest as his. My attorney was not an intellectual properties lawyer and did not cut me the best settlement. While the financial settlement was about what I would have been paid if I had collected what I should have plus the lawyer’s cut, the credits went to Richard Edlund and all rights went to Lucasfillm/Twentieth Century Fox. A man who became one of my closest friends and was an intellectual properties lawyer and he claims he would have cut a much more attractive deal, that would have included penalties for copyright violation.

We did eventually discover the reason for the numbers on the edge of the negatives, they were placed there by the photo lab that processed them in the first place. Those numbers were on the photos Edlund conceded were mine. They were also on the rest of the photos I claimed as mine and Edlund claimed as his, proving rather conclusively that they were mine, but that is not part of the official settlement.

So, I had the money, but no credits and no rights. I did, however, have the prints I had made with Gary Kurtz’ blessing. I gave a few away and the rest lay in an Ektacolor paper box for the next thirty three years.

Jack Warford

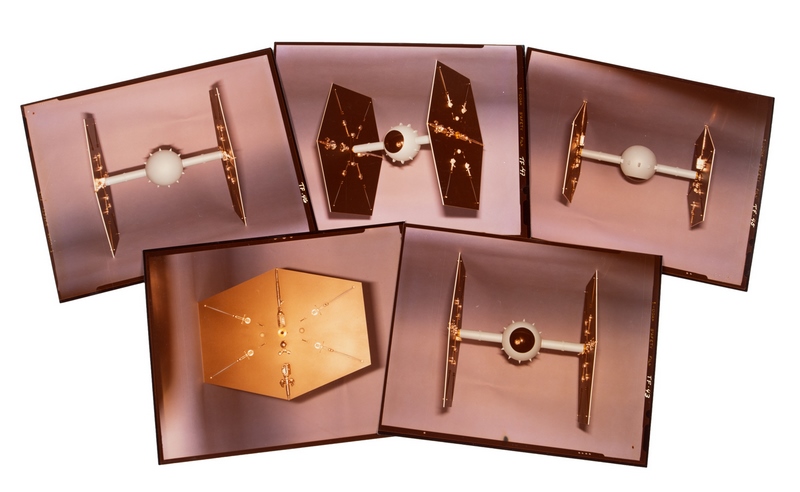

Below are some of the images that are part of his collection. Essentially, there were 19 total unique images made of the various starships represented in this collection, though all were produced in 1977 and some duplicated vary based on how they were developed and aging over time (though all were kept in photo boxes, so sheltered from sunlight all these decades later). The images in our catalouge are essentially photographs of photographs, so I can’t stress enough how stellar that they look in person (they are printed glossy, so extremely difficult to photograph without reflection and too large for us to scan):

Interestingly, I had mentioned Colin Cantwell, and he is very relevant here as well, in that Jack Warford was given a set of 148 unique 4×6 photos that he believed were taken by Richard Edlund before he was hired to do his own starship model photography. This extensive collection of 148 unique images also include photos not just of the filming models, but the prototype models created by Cantwell, offering some never-before-seen angles of these rare production pieces.

This first image is a collage of the collection, just to give an idea of the sheer number of different photos, and then sets based on each model:

These all go up for auction in a number of different sets on Saturday, July 18th at Julien’s Auctions. If anyone out there happens to know more about Jack Warford, his work on the films or anything about these images, please contact me – I’d love to know more myself.

Jason DeBord