Earlier this year, a story broke about the discovery that a genuine document produced by Abraham Lincoln had been altered in order to make it more historically significant. While the identification and preservation of historic documents is outside the scope of the same in the entertainment/popular culture memorabilia field, the story is instructive none the less, and highlights the ease with which genuine material can be altered to make it more important and valuable.

In the case of the Lincoln document, it has been reported by the Chicago Tribune and other mainstream media sources that a researcher in Virginia admitted that “he altered the date on a pardon to make it appear that the document was the among the last official business handled by the 16th president before his assassination, according to the National Archives” (see Lincoln expert admits altering historic document).

An official press release on the National Archives website details the story in full. The press release and accompanying images and video are republished below, and can be viewed directly at www.archives.org (see National Archives Discovers Date Change on Lincoln Record):

National Archives Discovers Date Change on Lincoln Record

Thomas Lowry Confesses to Altering Lincoln Pardon to April 14, 1865

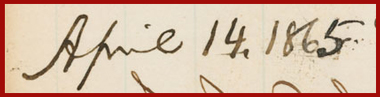

Washington, DC…Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero announced today that Thomas Lowry, a long-time Lincoln researcher from Woodbridge, VA, confessed on January 12, 2011, to altering an Abraham Lincoln Presidential pardon that is part of the permanent records of the U.S. National Archives. The pardon was for Patrick Murphy, a Civil War soldier in the Union Army who was court-martialed for desertion.

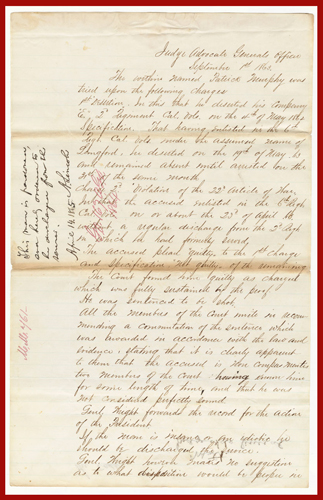

Lowry admitted to changing the date of Murphy’s pardon, written in Lincoln’s hand, from April 14, 1864, to April 14, 1865, the day John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC. Having changed the year from 1864 to 1865, Lowry was then able to claim that this pardon was of significant historical relevance because it could be considered one of, if not the final official act by President Lincoln before his assassination.

The images and video are in the public domain and not subject to any copyright restrictions.

Click for High Resolution Download via Archives.gov

President Lincoln pardon for Patrick Murphy, a Civil War soldier in the Union Army who was court-martialed for desertion. Records of the Judge Advocate General (Army) National Archives. ARC Identifier:1839980

Click for High Resolution Download via Archives.gov

Close up of altered date and Abraham Lincoln “A. Lincoln” signature from a President Lincoln pardon for Patrick Murphy, a Civil War soldier in the Union Army.

Click for High Resolution Download via Archives.gov

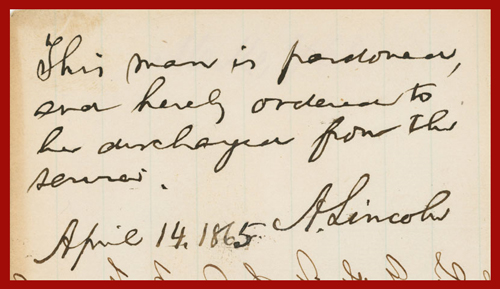

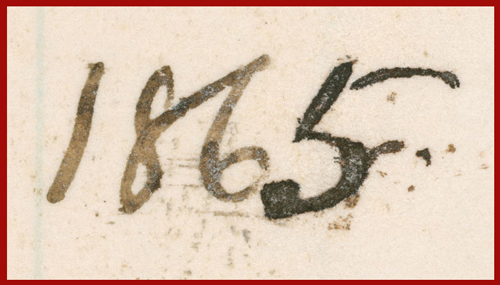

Close up of the altered date: Long-time Lincoln researcher Thomas Lowry admitted to changing the date of Murphy’s pardon, written in Lincoln’s hand, from April 14, 1864 to April 14, 1865. Records of the Judge Advocate General (Army) National Archives.

In 1998, Lowry was recognized in the national media for his “discovery” of the Murphy pardon, which was placed on exhibit in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in the National Archives Building in Washington, DC. Lowry subsequently cited the altered record in his book, Don’t Shoot That Boy: Abraham Lincoln and Military Justice, published in 1999.

In making the announcement, the Archivist said, “I am very grateful to Archives staff member Trevor Plante and the Office of the Inspector General for their hard work in uncovering this criminal intention to rewrite history. The Inspector General’s Archival Recovery Team has proven once again its importance in contributing to our shared commitment to secure the nation’s historical record.”

National Archives archivist Trevor Plante reported to the National Archives Office of Inspector General that he believed the date on the Murphy pardon had been altered: the “5” looked like a darker shade of ink than the rest of the date and it appeared that there might have been another number under the “5”. Investigative Archivist Mitchell Yockelson of the Inspector General’s Archival Recovery Team (ART) confirmed Plante’s suspicions.

In an effort to determine who altered the Murphy pardon, the Office of the Inspector General contacted Lowry, a recognized Lincoln subject-matter expert, for assistance. Lowry initially responded, but when he learned the basis for the contact, communication to the Office of Inspector General ceased.

On January 12, 2011, Lowry ultimately agreed to be interviewed by the Office of the Inspector General’s special agent Greg Tremaglio. In the course of the interview, Lowry admitted to altering the Murphy pardon to reflect the date of Lincoln’s assassination in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2071. Against National Archives regulations, Lowry brought a fountain pen into a National Archives research room where, using fadeproof, pigment-based ink, he altered the date of the Murphy pardon in order to change its historical significance.

This matter was referred to the Department of Justice for criminal prosecution; however the Department of Justice informed the National Archives that the statute of limitations had expired, and therefore Lowry could not be prosecuted. The National Archives, however, has permanently banned him from all of its facilities and research rooms.

Inspector General Paul Brachfeld expressed his tremendous appreciation for the work of Plante and the Inspector General’s Archival Recovery Team in resolving this matter. Brachfeld added that “the stated mission of ART is ‘archival recovery,’ and while the Murphy pardon was neither lost or stolen, in a very real way our work helped to ‘recover’ the true record of a significant period in our collective history.”

At a later date, National Archives conservators will examine the document to determine whether the original date of 1864 can be restored by removing the “5”.

The National Archives has also produced a video for publication – Inside the Vaults – National Archives Discovers Date Change on Lincoln Document:

As noted, while this falls outside of the identification, preservation, and collection of original pop culture memorabilia field, it underscores the ease with which even genuine material can be manipulated in efforts to defraud.

Many hobbyists and dealers of original entertainment memorabilia relay upon a number of things in order to authenticate a variety of material, including props, costumes, set pieces, and other items made for and used in film and television productions. This often includes documents such as letters of authenticity, certificates of authenticity, wardrobe and asset tags, garment labels, production invoices, and other items.

So while many may accept any of the above examples as fact, even if genuine, such items can be subsequently altered to significantly impact use, attribution, and a variety of other factors.

For example, a genuine hanging paper wardrobe tag may be altered to include scene numbers, which would enhance the value of the piece, in that it could erroneously be attributed to specific scenes – perhaps key/important scenes in the movie – or be done to inaccurately assign a significant amount of use when that may not be the case at all, or certainly not something that could be verified with the wardrobe tag in its genuine state.

Another example is with sewn in garment labels. Unremarkable wardrobe pieces are frequently sold on eBay for nominal sums of money which are insignificant in terms of the piece itself, who is was worn by (if indicated at all), and what production in which it was employed. A practice which has manifested itself within the hobby is the act of individuals buying such wardrobe pieces, carefully removing the garment labels, bleaching out the hand or typewritten notes, and writing new (fraudulent) information in its place, and attaching the label to a different wardrobe piece.

In both examples, an authenticator may determine that each theoretical example above is a genuine wardrobe tag or label and accept the information contained within at face value, when in fact altering such items can be done quite easily and can be very difficult to detect, let alone disprove.

Obviously, paper documents such as COAs and LOAs can be copied, reproduced, and altered with ease, given the cheap and sophisticated technology available to the public today. Of course, such items can also be completely manufactured as well, which is why authentication of original props and costumes from movies and television is extremely challenging, especially given the prevalence of “off the shelf” material used in productions and the value of such material in the marketplace. Even with wardrobe pieces, someone can simply write the name of a prominent actor on the manufacturer’s label as “proof” it was used in a specific production and worn by a star.

Of course, the Original Prop Blog has published literally hundreds of articles about these very subjects, and has even found certificates of authenticity from the same source with completely discrepant autographs.

In any event, the Lincoln document at the National Archives serves as an excellent reminder of the diligence required in authenticating any rare material that relies open a variety of factors, and it is important that those participating in this and related fields use all tools at their disposal in being part of the lineage and history of this material. In this case, the individual who altered the Lincoln document actually did so from within the National Archives, which makes the story all the more astounding.

Jason DeBord