Given the British High Court ruling on the case of Lucasfilm vs. Andrew Ainsworth (see Lucasfilm vs. Ainsworth High Court Ruling: Full Document from Royal Courts of Justice), and the additional information available from the court documents, I thought it would be a good opportunity to build on the prior OPB article exploring the “prototype” Stormtrooper helmets (see Star Wars “Prototype” Stormtrooper Helmets) trading in the marketplace as original and authentic precursors to the helmets used on set and filmed in Star Wars: A New Hope.

As noted in the original article, a number of Stormtrooper helmets characterized as “prototypes” and attributed to the production of the first Star Wars film, A New Hope. have traded in the marketplace. At public auction house events alone, there appear to be at least six such helmets. A number of hobbyists do not believe these helmets are actually prototypes but were made following the production of the first Star Wars film and not employed in any subsequent production, which would classify them as non-Original or replicas (see Replica Prop Forum topic, Star Wars “Prototype” Stormtrooper Helmets).

The original article served to archive photos and descriptions of these helmets sold into the marketplace, assembled additional relevant information, and analyzed the history and pedigree attached to these props. Sharing all available information was done with hopes of soliciting additional insights as well as invite commentary and initiate an open dialogue to hopefully learn more about these pieces and their origins and possibly make final determinations as to authenticity and prototype status.

High Court Statements on the Veracity of Mr. Ainsworth’s Recollections, Claims, Assertions

Reading the High Court ruling by Mr. Justice Mann (see Case No: HC06C03813), I thought it would be appropriate to quote some of the statements made by the judge in the ruling, to take them into consideration given that the “prototype” status and provenance assigned to these helmets trading in the marketplace that seem to have originated from and rely on the statements and claims of Mr. Ainsworth (see Christie’s December 2002 auction in South Kensington, Sale 9538 “Film and Entertainment”, Lot 217 – ref).

Pertinent excerpts:

15. However, in his evidence he betrayed that he has become somewhat obsessed with the present dispute, and that has led him to put forward versions of events which are reconstructions designed, wittingly or unwittingly, to support his case. His evidence on the events of 1976 changed on a number of occasions. In one sense that is not surprising. Having a detailed recollection of events which took place over 30 years ago is difficult if not impossible, and any purported recollection of detail (and indeed of general patterns) must be viewed with caution.

~

His process of reconstruction, however, betrays a vigour in his approach which puts him more in the role of advocate than witness.

~

This incident, and others, demonstrates that Mr Ainsworth is always looking for a gloss on, or analysis of, evidence which will favour his case.

16. His attempts to play up his part, and to play down Mr Mollo’s part, in the creation of this helmet is a good example of his viewing events through his own Ainsworth-tinted spectacles

17. He also demonstrated a tendency to take credit for things that he was not entitled to in other ways.

~

His statement was therefore untrue, and plainly so. Furthermore, he did not acknowledge that there was anything wrong with his witness statement in this respect. He was either being dishonest about that, or he has a strange subjective view of the truth which calls into question his reliability as a witness in relation to such matters.

19. These particular points are not just general credibility points. They are credibility points going to a central issue in this case, namely the reliability of Mr Ainsworth’s evidence as to his alleged design of some of the relevant material in this case. He has clearly demonstrated that he is prepared to claim more than he is entitled to in other contexts. I have to bear that firmly in mind in considering his claims in relation to the designs in issue in this case.

20. Immediately before he went in the witness box, he produced more evidence in the form of a marked up version of his first witness statement, showing deletions and additions that he wished to make. Some of them were minor; many of them were not. They amounted to very material variations from the first witness statement, for whose truth he had vouched in his statement of truth. That, of itself, might not be a factor going to credibility, but the number and nature of the changes means that in the present case it is.

21. All these factors, and other challenges made to his credibility during the case, make me approach Mr Ainsworth’s evidence with a great deal of caution.

36. I think that this is another example of Mr Ainsworth’s propensity to claim authorship of ideas with no real justification for doing so.

46. I do not accept Mr Ainsworth’s evidence on this point. I think that his factual case is born of a combination of loss of recollection over time, and his propensity to claim credit for greater creativity than he in fact demonstrated.

54. The first observation I would make is that Mr Ainsworth’s version of events is intrinsically unlikely.

~

For those reasons alone, therefore, I think that Mr Ainsworth’s version of events is not probable. However, it becomes even less probable when one sees that in Mollo’s notebooks there are drawings which are plainly intended to represent at least some of these subsidiary helmets.

56. I do not rely much on these particular timing points. Mr Ainsworth’s putting the timing as early as 23rd January is a matter of reconstruction from other matters, principally from his records of ordering material. It is not at all convincing.

~

That is another reason for not accepting Mr Ainsworth’s version of events about this. I consider that his claims to authorship of these helmets is yet another example of his propensity to make excessive authorship claims.

67. No-one has a particularly clear recollection of any detail relating to this [cheesegrater-type] helmet. When he did his first witness statement Mr Ainsworth had apparently forgotten that he ever made prototypes at all. Working out what happened is therefore a question of ascertaining the probabilities, with such assistance as the contemporaneous documents provide.

69. As the trial progressed Mr Ainsworth claimed that the cheesegrater in court which was said to have been the original made by him was not made by him. He said that the earpiece was different and was not that originally used in the film, that the plastic material was not the same as he used, and that it demonstrated methods of construction or alteration that he would not have used. That challenge largely evaporated when it was demonstrated (by carefully playing parts of the film almost frame by frame) that the earpiece was indeed the original (and that the one used on his modern reproduction is not the same), and that scientific tests demonstrated that the material used was indeed the material used by him (and he retracted his allegation to the contrary). At the end of the day this somewhat expensive side-show did not go directly to any of the issues in the action, but it did demonstrate the inappropriate vigour with which Mr Ainsworth pursued allegations on the basis of imperfect (or non-existent) recollection. He even went so far as to suggest that parts of the film had been digitally remastered or had been re-shot using different cheesegraters (with nothing but guesswork to go on) or that the studio had changed just the earpieces on the helmets (which was implausible in the extreme). All this demonstrates the great care which has to be brought to bear in considering his evidence and his reconstructions. It also demonstrates his unwillingness to accept he has been mistaken. The earpiece of the helmet used in the film differs in detail from that on the prototype, as I have mentioned above. Mr Ainsworth’s modern helmet uses the prototype version, not the final one. Mr Ainsworth insists to his public that he is faithfully using the original moulds as used on the film version. That cannot be the case in respect of this piece of detail; but he was reluctant to admit it. All that is detail, but it is detail going to Mr Ainsworth’s credibility in important areas.

References to the Prototype Stormtrooper Helmet in the Ruling

The ruling also include information pertaining to the prototype Stormtrooper helmet and overall development of the helmet during production of the film.

33. One of the people to whom they turned was Mr Pemberton. He was asked to go to the studios to meet Mr Lucas, probably on 6th January 1976. Mr Lucas showed him the two Mr McQuarrie paintings referred to above and asked him if he could produce the Stormtrooper helmet shown there. He went away in order to do so and started to sculpt a clay head, basing himself on the Mr McQuarrie paintings. He showed his first attempt to Mr Lucas a few days later, and Mr Lucas made certain observations on it. Amendments were carried out and another version was shown to Mr Lucas, of which he approved at a third meeting between the two men. In the evidence there is a photograph of what is probably Mr Pemberton’s clay head, with Mr Lucas studying it from behind. It has some of the general shape, but not the sort of “facial” detail that one sees in the final version of the helmet. It is not clear at what stage of the sculpting that photograph was taken, or what extra detail was subsequently added, but it is plain that Mr Pemberton was following pretty closely the design of the helmet as shown in the two paintings. It is also plain that Mr Lucas had to be satisfied about the appearance of the helmets.

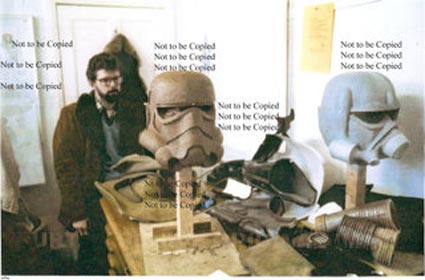

The referenced photo is likely the one published in the original article published on this subject:

Note that there are two clay sculpts, which is consistent with the excerpt from the High Court ruling. Per the ruling, these were produced prior to any involvement from Mr. Ainsworth.

34. At the third meeting Mr Lucas asked Mr Pemberton to produce a quantity (probably 50) of the helmets. Mr Pemberton did not have the time or, more significantly, the expertise to manufacture a real version himself, so he turned to Mr Ainsworth, who worked and lived 2 doors away and with whom he had had some prior dealings. He respected Mr Ainsworth’s ability to work with plastics. Mr Lucas was told by him that he would be able to arrange for the helmets to be made, but Mr Ainsworth was not identified to him.

35. On or about 20th January Mr Pemberton spoke to Mr Ainsworth about the making of the helmet. He explained that he had a customer who wanted a helmet as a prop, and showed him, and provided him with, good reproductions of the two Mr McQuarrie pictures and his clay model. Mr Ainsworth says that the clay head did not have much detail on it – it did not have eyes, or ears, or any indication of surface finish. Mr Pemberton was unable to say precisely what his head looked like when he handed it over, it terms of the details conveyed. I am, however, satisfied on the probabilities that it was a reasonable 3D rendition of the Stormtrooper in the Mr McQuarrie paintings. The Stormtrooper was a key character in the film, and Mr Lucas is likely to have wanted to see some significant level of detail in its realisation before approving the clay head. Mr Ainsworth was asked if he could produce a helmet in accordance with the drawings and clay head, and he agreed he would produce something. Mr Ainsworth says that the customer was not identified at that time, and he did not even know it was being produced for a film. He thought that it would be used in a play. This was not materially challenged, but the significant thing is that he appreciated that it was a thing for a dramatic production by a customer of Mr Pemberton.

36. Mr Ainsworth spent a couple of days producing a prototype. He worked from the material he had been given by Pemberton, but added some detail of his own. He had to consider the practicalities of production. The helmet was produced in five parts – the face, the back/crown, an ear piece on each side and an insert piece for the eyes. One of the functions of the separate ear pieces was to cover the join of the other principal parts. They were one aspect of detail where he did not reproduce what was apparent from the McQuarrie drawings. He added his own refinements of precisely how the facial detail was to look – he produced the precise detail of the “frown” (the apparent nasal region), decided how precisely to produce the effect at the “mouth” and on each side (for the latter he used microphone ends) and he decided to use a black rubber moulding (from a car part) above the eyes (the drawings did not contain a black feature there). His initial evidence sought to portray him as being the person who “convinced” Lucas to use white for the helmet (and the armour). He said that he had thought the drawings portrayed silver armour. Whatever he may have perceived as the colour in the drawings, it is quite clear from the evidence that Lucas had already decided to use white. Lucas therefore needed no persuading or convincing, and in his cross-examination he very much toned down the statements in his witness statements about this. I think that this is another example of Mr Ainsworth’s propensity to claim authorship of ideas with no real justification for doing so.

Note that the ruling states that Mr. Ainsworth produced “a” (singular) prototype.

Very critical is the statement that “[t]he helmet was produced in five parts – the face, the back/crown. an ear piece on each side and an insert piece of the eyes.”

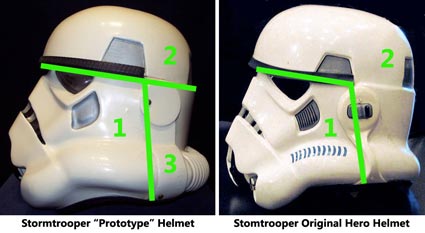

In the prior article, I showed the distinctions between the original and authentic helmets seen in the film compared with these “prototype” helmets trading in the marketplace. As shown in the prior article, the back and crown of the authentic helmets used in the film was one piece, while it was two pieces with the “prototype” helmets:

Note: Original Hero helmet at right from LucasFilm Celebration IV, photo by “Shadow”

The original Stormtrooper helmets seen in the film were made of three main parts:

- a face mask (below “brow”, to front of “ear cap”)

- top or crown (above “brow) and back (behind “ear cap”)

The “prototype” Stormtrooper helmets were made of two main parts:

- a face mask (below “brow”, in front of “ear cap”)

- top or crown (above “brow” line, front to back)

- back (under “brow” line, incorporating “ear cap”)

The original helmets featured “ear caps” which covered the seam created by attaching the two parts, just as the black “brow” trim covered the seam between the face mask and the top cap or crown section.

The “prototype” helmets feature a more advanced design in which the “ear piece” is part of the back, rather than being an extra piece added to each side in order to cover a visible seam.

What the High Court describes in the ruling, as a prototype, is a helmet constructed as the original helmets were made for and used in the film – not what is now trading in the marketplace as a “prototype”. The two key differences being the one-piece crown and back (compared with two pieces with the “prototypes”) and the separate ear piece to cover the seams on the side (compared with no separate ear pieces on the “prototypes”).

The five piece construction is reiterated in the next excerpt from the ruling:

37. Be that as it may, Mr Wilson, on behalf of Mr Ainsworth, did not dispute that the helmet thus produced (and the final version) was a substantial reproduction of the McQuarrie material for copyright purposes; and Lucas did not dispute that some of the detail on the prototype and the final version was created by Mr Ainsworth. I received a lot of evidence from Mr Ainsworth as to how precisely he first produced his own version of the helmet, and how he then went on to make the various moulds which he used for vacuum-forming the five parts which made up the whole. In the end little of that detail mattered, in relation to the Stormtrooper helmet. What is important is the source of its design. During the process of making the prototype Mr Pemberton’s clay head was destroyed in some sort of accident. Again, nothing now turns on this, since on any footing the Mr Ainsworth helmets were substantial copies of the McQuarrie drawings.

39. Mr Ainsworth made several prototypes as he tried to get to a satisfactory design. In his first witness statement he suggested that he gave a prototype to Mr Pemberton at the beginning of February, and the latter in turn showed it to Mr Lucas. However, having studied Mr Pemberton’s diary closely, along with Mr Mollo’s diary entries, Mr Ainsworth changed the chronology and participation of the parties significantly. Having originally portrayed the situation as one in which he did not know who the end user was, and in which he did not meet Mr Mollo until mid-February, he then suggested that he met Mr Mollo as early as 23rd January. He also materially shifted the date on which he said he was asked to create other helmets from March to this January date. Whether he was right about that, I think it likely that he did meet Mr Mollo before mid-February. They probably met in the last week of January, either at Mr Ainsworth’s premises or at Mr Pemberton’s, and that enabled them to have a discussion about the then form of the prototype helmet. There was discussion about further modifications to the design – Mr Mollo accepted, and indeed asserted, that there were changes which were discussed between him and Mr Ainsworth. There was an exchange of ideas, probably over the next week or two, leading to the presentation of what seems to have been a final prototype to Mr Lucas on 17th February. There was a dispute as to the date when the first prototype was handed over, but the precise date does not matter; it was at some point within the last 10 days of January 2006. There may have been a little discussion over the modification of detail. Mr Lucas, who was still exercising the close and detailed control that he had hitherto exercised, approved the helmet by 19th February and he and Mr Mollo said that they wanted 50 of them. They dealt with Mr Pemberton in relation to that. Mr Pemberton told Mr Ainsworth that he wanted 50 helmets and Mr Ainsworth quoted £20 per helmet. Mr Pemberton said he would have to get back to his customer about that and a couple of days later the price was approved. Mr Ainsworth set about making the 50 using his moulds and vacuum moulding machinery. Some were made in a khaki plastic and painted white, but that was less than satisfactory because the paint tended to come off, so he made most in white ABS. They were delivered to the studio during March and Mr Ainsworth invoiced Mr Pemberton for them. He was duly paid. More were produced later.

Summary

While this new information, insights, and opinions do not address all of the outstanding questions posed in the original article on this topic, it does contribute to the ongoing dialogue about these “prototype” Stormtrooper helmets and the accompanying provenance assigned to the props by Mr. Ainsworth and the auction houses that have marketed and/or sold them.

Jason De Bord

Prior Original Prop Blog articles related to these developments can be found here: