Writer and original prop collector Ron Magid has authored a number of articles in the L.A. Times, which may be of interest to other hobbyists. These articles are under the “How’d They Do That?” and “Scene Stealer” headings.

December 6, 2007: Re-imagining Times Square in ‘I Am Legend’

December 9, 2007: Effects artists go with the flow to keep ‘The Golden Compass’ on course

December 13, 2007: Shivers cast in silver for ‘Sweeney Todd’s’ shivs

December 23, 2007: Behaving like a zombie in ‘I Am Legend’

December 27, 2007: The Kite Runner

I have noticed some of these articles are in abbreviated form, and not sure how long they will be available online, so here is an example of one of the articles below (direct link to L.A. Times version):

Scene Stealer: Sweeny Todd

By Ron Magid, Special to the Times

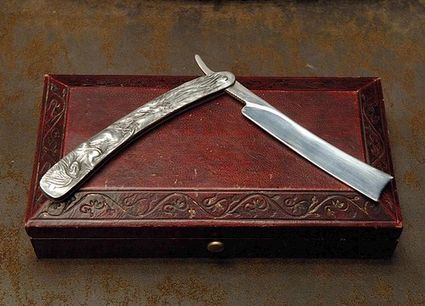

Look sharp. These are no ordinary razors but exquisite instruments for slitting the throats of Londoners, whose perceived crimes against one Benjamin Barker drove the barber to wield his blades with deadly purpose under his nom de mort, Sweeney Todd.

The demon barber of Fleet Street’s tools of the trade: a seven-blade matched set (one for each day of the week) housed in a simple leather box. The ensemble, featured so prominently in “Sweeney Todd,” opening Dec. 21, is the work of prop master David Balfour, who previously built “The Da Vinci Code’s” elaborate Codex and whose “lifelong dream” was to collaborate with Tim Burton.

Burton’s take on Stephen Sondheim’s Grand Guignol musical — wherein Sweeney’s late customers plunge through a trapdoor beneath his barber chair into the supply room of Mrs. Lovett’s pie shop, their remains repackaged as tasty meat tarts — sent Balfour seeking some unusual inspiration: a painting by the great poet and artist William Blake, “A Vision of the Last Judgment.” “Blake is a complex, troubled character,” Balfour says. “I thought [his work] would be quite apt for the feel of these razors.”

Here’s how Balfour and company helped Sweeney swing his razor high.

To grace Todd’s razors, Balfour drew up seven melancholy, attenuated bas-relief angels. “It seemed traditional to do engraving on the knives. I felt these unusual, haunting and mystical-looking figures lent themselves to the shape of the handles.”

After Dick George sculpted prototypes of the set, Burton selected two hero handles. “One was a mother and child, which relates to Todd’s missing family, the other was a serene female figure, her face tilted, her flowing hair clinging to her body. We worked very closely on the designs with Tim.”

The casket where the seven deadly razors repose was based on a Victorian leather box. As for the blades, “Tim had a very specific idea of their size: bigger than normal razors, just for the effect, but not too oversized” as to draw attention, Balfour says.

After Burton and Johnny Depp approved the prototypes, Balfour built several stunt versions from plastic and rubber but cast the hero razors in metal. In the story, Todd’s blades are made from “chaste silver.” How about Balfour’s props? “They were, yes,” he says.

Would this climactic moment — when Todd raises his razor heavenward, exclaiming, “At last, my arm is complete again!” — have been half so hair-raising if the blades hadn’t passed the Depp test? Balfour doesn’t think so: “Johnny is very meticulous and very aware of his props. You couldn’t pass off anything that wasn’t right.”

Depp impressed Balfour with his research. “He knew how to hold a razor,” he says. “I’m sure he could’ve shaved somebody quite successfully.”

Anybody but Balfour. “His performance made me think twice of taking a shave with an open razor!”

I am looking forward to following future articles.

Jason De Bord